Reading time ~ 7 minutesI’m a big fan of Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints for getting important improvements made in the most suitable order for a team. Our current scrum board is the result of focusing on the most evident, soluble problem each day for a couple of weeks. No grand plan, just good emergent design.

Note this is a very long article as some readers of part 1 asked for all the details as soon as I could get them written, today’s the first time I’ve been near my blog in a week. I’ll switch back to shorter posts after this for a while.

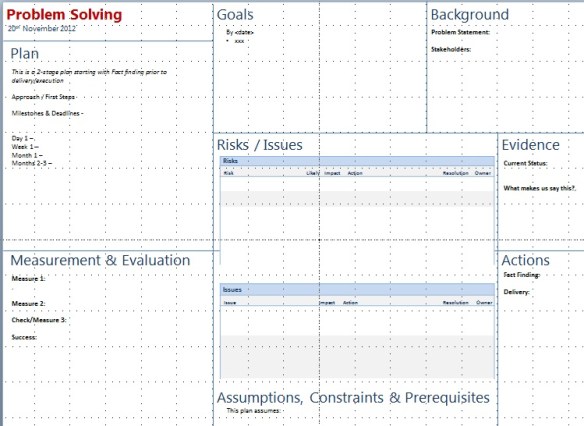

Here’s an in depth look at each of the areas of our board…

Using the peripheral space for useful stuff

Feedback

A single sticky with a quote regarding some feedback. The last 3 sprints we’ve left one up there that says “It shouldn’t be all that hard” . A reminder not to generalize (“it” was much harder)

Theme

One sticky. Our current theme is “Contact Management”, The next will be “Dashboarding” or similar. Just a little reminder of what the overall focus of the sprint or sprints is. This helps when clarifying or controlling scope, questions, debt & defects.

Capacity

During sprint planning we look at who’s in, when and what other commitments they have (beyond the usual overheads and maintenance activity). Capacity is calculated in half-day (4-hour) increments for each of us, totalled up as a whole team in hours. We then subtract 40% for overheads & support.

We track a second capacity number under the first which is the actual total effort hours of tasks completed in the last sprint. Generally this is a fair bit lower than the forecast.

The differences between these two figures are useful input for understanding our capabilities & overheads.

We limit tasks during sprint planning to around 70% of our maximum delivery capacity or close to our previous delivery capability in order to leave space for unknown / discovered activities and hurdles. If planning another story would take us over this level, we hold off until we’ve actually been able to deliver the first – there’s no point in breaking stories down into tasks if they’re highly unlikely to happen in the next 2 weeks.

If we really do well, we can always reconvene.

Tags

At the moment we have 2 sets of tags on the board; “Blocked” and “Please Test”. The team no longer uses the “please test” tags so they’re likely to be removed this week. We assume coding tasks include developer-led testing activity and any other testing is planned in as scheduled tasks. This has reduced dev-test handover as the whole team focuses on the set of tasks required to complete a story, not their individual tasks.

I’m likely to add “red tags” soon for tasks that need particular focus or expediting. We’ll limit the use of red tags to one WIP item at a time and only when needed.

Key

A color key for our tasks. Currently we have

- blue : code & test

- green : design & ux

- yellow : test

- orange : management noise

- pink : support & bugs

Stories

The top horizontal swimlane of our board contains stories and story activities. The left-most column of this contains story cards in priority order from top to bottom for stories planned for this sprint. The space here is deliberately small. The last 2 sprints we had only 2 stories listed, in the next sprint we’re actually reducing it to 1 and having the whole team pull single stories through. (Update – We ended up pulling single stories as a flow after this point right to the end of the project)

“Extra”

A placeholder for “extra” stories.

If we really do clear all the stories on the board, this area is a placeholder in rough priority order for the next 1 or 2 stories we might play. These are not broken down into tasks unless there’s certainty that we’ll actually work on them in this sprint.

Physical Holders

A more traditional lean technique. We have an individual holder for 1-2 pads of each color of stickies. We can quickly see if any are running low and replenish stock. We also have a holder for story cards although that’s rarely used (we generally don’t add stories when stood at the board).

There’s also a holder for pens. We ensure there’s enough marker pens in the holder for everyone to have one during our standup and we ensure that there’s one of each whiteboard pen color needed for drawing graphs and totals on the board.

Hours (on stories)

This is the initial estimate in effort hours of all tasks we identified prior to & during sprint planning that went onto the board at the start of the sprint. We compare these with total hours completed at the end of the sprint to learn from and improve our tasking and estimation.

Over time we hope to gather enough data to see the typical ranges of hours spent on stories of each size (we expect a bit of overlap)

Sprint Tasks

Our second main horizontal swimlane is “sprint tasks”. These are all the activities required by us as a team in order to be able to complete the sprint and usually deploy our working software to production. We also tend to add extra technical debt cleanup items into this swimlane.

This approach seems better at the moment than having specific (and artificial) stories for these activities.

It’s up to us how much trade-off we have between sprint tasks and story tasks in a sprint. Since creating this swimlane we’re finding 40-60% of our effort is going into this area however this is because we’ve been prioritising some technical debt and deployment improvement activities. That rate will adjust over the next couple of sprints.

Support/Bugs

The bottom swimlane on our board is for support issues and bugs. Right now we’re not using this very much as our support and old bug fixing activity has been relatively low.

We’ll see how useful this lane is longer-term.

Note, bugs related to work we’re actually doing are either fixed immediately and not added to the board at all or are added into the stories swimlane relevant to the story they’re found in.

Todo/Next/WIP/Done

Todo, WIP and Done are the typical status lanes for tasks you see on most boards these days. “Next” is an addition we added in very early on and has been a bit of a game-changer in managing the flow of tasks effectively here’s a link to the full article on the “next” column.

Retrospective Input

I talked a little bit about this at the UK Agile Coaches Gathering this weekend and I’ll expand more in a standalone article shortly. Put simply, we found that getting potential retrospective input visible every day during the daily standup has been more effective in driving continuous improvement and makes it easier to collate retrospective data at the end of the sprint. Mike Pearce also recommended something similar over the weekend – maintain your release and sprint timeline with pitfalls and lessons so that there’s less head-scratching at the end.

Graphs:

We’re tracking burn-down of task hours for both sprint tasks and story tasks in parallel (different colors). Then on the same graph we’re also tracking the burn-up of total capacity. It’s working okay for us at the moment but I can’t help thinking it’s still not quite right so I’m sure we’ll revisit this.

Beneath the burn-up/down we’re tracking per-sprint velocity as a basic bar chart. Straightforward, simple, easy to complete and easy to understand.

Sprint Schedule / Countdown boxes

As of the end of the last sprint we removed the sprint schedule, the list of historic dates wasn’t adding anything for us. We have the current sprint dates at the top-left of the board instead and have used this space for a set of countdown blocks 10..1 with effort hours to do and forecast remaining each day. This gives us immediate feedback as to whether we may have a problem in meeting the end of the sprint with current task scope. I’ll write up the experience on the countdown boxes separately once we’ve been using them a while.

“Done Done”

This serves a couple of subtle purposes…

There’s something very satisfying about taking tasks from the board and dumping them in the “done done” box.

We clear down the board into “done done” at the end of each sprint. This makes it clear that we’re not really done until we’ve completed everything and cleared the decks.

Although the box itself is basically a trash holder, it serves as a constant reminder that we’re not done until we’re done 🙂

We’ve added a few more things since I drew the original picture of our board…

Running Totals

After the daily stand up we sum up the total effort hours for each horizontal/vertical swimlane square/block and scribble those on the board. We can then transpose these into tracking graphs.

Right now we only track todo by horizontal lane and overall done but we have the data available for cumulative flow tracking if we feel the need.

Debt

We’ve added a very small space for newly accumulated or discovered debt related to our current work. It’s deliberately small to keep things minimal. When it fills up we’ll need to do something with it (if not sooner). It gives us one more line of slack if things go unexpectedly in a sprint for some reason whilst we still focus on deploying working software. This is still a running experiment but the intention is to treat this like credit card debt – it’s a short-term postponement mechanism, not a backlog.

Next Sprint Tasks

In much the same way as we have “extra” stories, we’ve added a placeholder for tasks we need to do in the following sprint but don’t have capacity for right now. This stops us overloading the current sprint tasks lane once things start moving without forgetting important future activities.

An Update (November 2013)

I’ve been rooting through my old photos and found a picture of the board toward the end of the project (September 2012) so you can see what it *actually* looked like as it evolved beyond what I’ve described above.

If you’re interested in even more whiteboard designs (and how they evolved over time) take a look at “A Year of Whiteboard Evolution”.

Closing Comments…

Don’t be afraid to adjust your working area if things don’t seem to be flowing right.

This isn’t the end for our board adjustments, what we’re using will certainly be different in a few weeks time however today it serves our needs well and must remain simple enough for new team members to understand.

I strongly recommend reading Henrik Kniberg’s recent book . I read the review draft last week (July 2011) and saw close similarities in the board structures the PUST teams at RPS were using and what we have here. I also share the same view as Henrik that each team – even within the same group – should be free to choose their own board style.

. I read the review draft last week (July 2011) and saw close similarities in the board structures the PUST teams at RPS were using and what we have here. I also share the same view as Henrik that each team – even within the same group – should be free to choose their own board style.

Try taking a few of these ideas away to experiment with but you probably won’t need them all.

Without any reading at all, the 3 strongest options stood out. Better still, this technique didn’t need anything more than expertise and instinct. I’m free to follow up with further research and evidence if needed but at that point we were after a first-cut and a quick narrowing of options to focus our efforts.

Without any reading at all, the 3 strongest options stood out. Better still, this technique didn’t need anything more than expertise and instinct. I’m free to follow up with further research and evidence if needed but at that point we were after a first-cut and a quick narrowing of options to focus our efforts.